Wetland Restoration Begins in Little Yellow River Watershed

By Mark Pfost, Public Lands Ecologist – mpfost@wisducks.org

By Mark Pfost, Public Lands Ecologist – mpfost@wisducks.org

This article originally appeared in Wisconsin Waterfowl Association’s October, 2024 Newsletter edition.

WWA is set to take on its largest wetland restoration project ever! Wisconsin Waterfowl Association recently entered a cooperative agreement with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to restore wetland hydrology on thousands of acres of Juneau County public lands.

To understand this project, it is first necessary to understand what happened one-hundred years ago, early in the 20th Century. Following the logging “boom,” speculators and settlers saw the recently-cleared land as business opportunities. The dark peat soils looked fertile, but they were too wet to farm. So, the state’s first official drainage district formed and then designed a network of ditches which eventually drained sixty thousand acres of land. The Little Yellow River and Beaver Creek were deepened and straightened to help carry away water received from miles of ditches. Organic soils dried out and then burned up. In no time, the soils were depleted and farmers went broke. Some sold their farms and moved; others simply walked away. The “drainage dream” became a nightmare, and the county became responsible for abandoned lands, and local townships took responsibility for maintaining the roads.

In 1939, the federal government purchased about 110,000 acres of land from the county and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service set it aside for wildlife conservation. Forty-four thousand acres became the Necedah National Wildlife Refuge and the Wisconsin DNR agreed to manage the remainder as Meadow Valley State Wildlife Area. The agencies worked to improve wildlife habitat. They replanted forests, managed grasslands with prescribed fire, and constructed impoundments to manage water levels, but they did little to undo the damage of the drainage network.

In 1939, the federal government purchased about 110,000 acres of land from the county and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service set it aside for wildlife conservation. Forty-four thousand acres became the Necedah National Wildlife Refuge and the Wisconsin DNR agreed to manage the remainder as Meadow Valley State Wildlife Area. The agencies worked to improve wildlife habitat. They replanted forests, managed grasslands with prescribed fire, and constructed impoundments to manage water levels, but they did little to undo the damage of the drainage network.

Ever since, townships have struggled “in a game of inches” to maintain the low, sandy roads in the face of heavy precipitation events, undersized culverts and beaver dams. Roads flood frequently or wash out, and beavers plug culverts. The various government entities (federal, state, and local) viewed the problems and the solutions differently. Was it important to maintain all the roads? Were the ditches helping or hurting the situation? Was there a way to have wetlands and dry roads?

Not long before Covid, Necedah’s wildlife biologist Brad Strobel began thinking about restoring the Little Yellow River. The river, a casualty of the drainage dream, had spent the last century as a turbid, moribund ditch with little to no wildlife value. At this time Strobel’s office was about ten feet from mine. We’d frequently use each other to chew over aspects of our respective restoration ideas; my private-lands projects or his on-Refuge projects. Discussions led to action, and in 2019 the Refuge began restoring the first mile of the Little Yellow River. Seeing large flocks of mallards working up and down the newly restored river told us that our ideas were working. Since then, the Refuge, with help from the DNR, restored four miles of the West Branch of the Little Yellow. [to see a story map of this work visit: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/fa9735d899af4ae0940e5c191ecc20be)

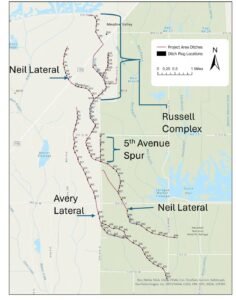

Our conversations didn’t stop when I retired from USFWS, but they moved from offices to duck blinds or over an evening beer. When WWA and the DNR signed the agreement to restore wetlands on state owned/managed lands, my thoughts turned to the miles of ditches that were draining wetlands on Meadow Valley. Simultaneously, Strobel was thinking of the same ditches and how they increased the quantity of water flowing in the Little Yellow River, well beyond its historic channel capacity. The unpredictable timing and amplitude of high-flow events down these ditches also increased road-infrastructure costs for the townships, consuming money they didn’t have. Eventually, all parties began seeing wetland restoration as a potential solution to the problem. Strobel applied for grants, and I kept WWA informed on progress and possibilities. The project design is now completed, the permits are in hand, and we have the funds to proceed. We’ve begun the process to elicit bids for construction. Construction may be able to start this winter—weather and contractor availability can’t be foreseen.

The project has both conservation and community benefits. Rewetting thousands of acres of wetland upstream from the Little Yellow will increase waterfowl habitat and benefit many other wildlife species. These wetlands will also act as a sponge, soaking up heavy rain events, and as a filter through which water will flow. The wetlands will be better able to capture atmospheric carbon. Moderated flows will pass downstream more gently, causing less strain to transportation infrastructure. Fewer tax dollars will be spent to make the same road repairs over and over again.

Waterfowl hunters will have more productive wetlands to hunt, and given the project’s size, an opportunity to find quietude and solitude in an area recovering from the drainage dream.